Hello, my lovely friends. March has been a very busy and exciting month,

with nine publications, radio shows, reviews, and poetry readings. I’m so

pleased to share with you all the latest and greatest:

I usually make these round-ups chronological, but I am just so excited

about this one, it’s going front and center: I am the featured poet in the

latest issue of Loud

Zoo, with five poems and the most thoughtful, in-depth interview I’ve ever

had the good fortune to participate in, starting on page 39. The five poems

are, “Garbage Pail Kids,” “Southpaw,” “Linda Martinez and Ed McMahon Say Hello

from the Afterlife,” “No, I don’t have a foot fetish,” and “Grandma’s Fan.”

But that's not the coolest part. The coolest part is the amazing music

composed by Tripp Kirby of The Electric Lungs to accompany the poems! They can

be listened to on the magazine site, or go directly to Sound Cloud.

Special thanks to Tripp for the awesome collaboration! If you haven't listened to his music, I highly recommend Don't Be Ashamed of the Way You Were Made. I might be a little obsessed. Also, big thanks to editor Josh Smith for pulling this all together.

I had three poems appear in The Woven Tale Press, “Crystal River,” “Super

Blue Blood Moon,” and “Buddhas on Death Row.” They are on pages 9-10 of the digital

copy. The print version is available here. “Buddhas on Death

Row” was also accepted for their monthly

spotlight. Many thanks to their team for continuing to support my work.

For those who don’t know, “Buddhas on Death Row” was inspired by my pen

pal, Moyo, who has been on death row in Texas for 18 years. While incarcerated,

he has become a Buddhist and an artist. His work has been displayed in various

galleries in the US, Finland, and the UK. He is currently working with at-risk

youth, and taking classes to become an educator. Learn more about his art at www.buddhasondeathrow.com.

My poems, “Therapy” and “The List” appeared in Alien

Buddha Press.

“Bug Out” and “Low” appeared in Anti-Heroin

Chic.

I had two short stories in Ariel Chart Magazine, “Astronomical

Events” and “The

Little Holly Market.” Editor Mark Antony Rossi messaged me to say, “Your

fiction pieces are ranked 2 & 3 this month in reads. That’s not the norm.

Usually poetry beats fiction. Thanks for being so damn good.” I want to give a

shout-out here to Mark, who has published my work before. He is also the force

between the Strength to be

Human podcast.

“Moon

Song,” “Faces,”

and “The Nostalgia Project” were published on Stanzaic Stylings. This

rounds out the series of six that were published on that site. Thanks so much

to editor Joanne Olivieri, it's been fun! “The

Nostalgia Project” also appeared this month on Duane’s PoeTree Blog.

And my last publication was in the TOUCH

issue of memoryhouse, two poems: "Brain Ghosts" and "Resonance."

Voice of Eve Magazine, which had previously published my poetry, gave West Side Girl & Other Poems a

five-star review.

I can also be heard on Songs of Selah, an online radio show. I called in during the open mic portion in the second hour of the March 12 episode and had a fun

conversation with host Scott Thomas Outlar and featured poet, Duane Vorhees. I read my poems, “Kitten Love” and “New Year’s Eve Talamada.”

I was at the Last Monday poetry reading at the Penn

Valley Quaker Center. It’s a monthly open mic that’s been running for almost

thirty years, and one of my favorite groups. If you’re in KC sometime, I hope you

stop in for a listen!

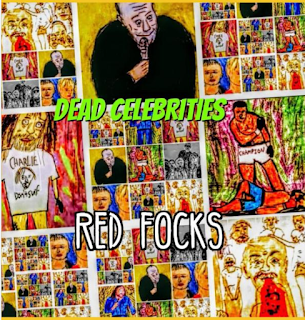

And finally, ICYMI, I posted three reviews on my blog this month, (Letters to Joan, Dead Celebrities, Ghost Train), as well

as a micro-essay (Supernatural). If you haven’t read those already, I hope you do.

My blog schedule is always a moving target, but what I have planned for

the near future are: more poetry reviews, another micro-essay and maybe some

O4S-related stuff.

Thank you, as always, for your readership!